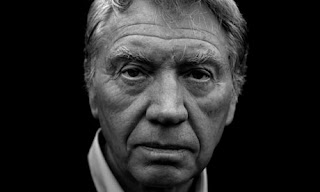

This is a passage from Don McCullin's autobiography, Unreasonable Behaviour. Since the end of the 1950s, McCullin has been a press photographer and documented conflict in Vietnam, Cyprus, Cambodia, Jerusalem and Northern Ireland. He is speaking above of the scenes he witnessed in Biafra in 1970 and his encounter with starving children dying collectively in a mission there as he recovered from malaria. McCullin faces the same dilemma I have heard many photographers voice over the years: when do you put down your camera and do something to help? When do you stop being a mere witness to conflict? In a recent film about his life and work (On the Edge of Reason) it is clear that McCullin has been seriously affected the horrors he has seen. Asked how he sleeps, he answers that he sleeps well; it is during the day time when his eyes are open that he remembers the dead and the dying. His darkroom, he says, is haunted by all the ghosts in his photos, and he now devotes his life to documenting the countryside around his home. However, he only has to hear a car backfire or a gunshot to be be sent back instantly to Vietnam or Biafra.

|

| Don McCullin |

My interest in wars and revolutions as historical phenomena is long-standing. As I wrote recently in another blog, my first substantive memory of watching, understanding and liking movies is at age about five or six, and the film in question was a Sunday night television screening of The Battle of Britain. A succession of Sunday afternoon war films, inevitably starring John Wayne, John Mills or Richard Attenborough, followed, and I watch these films again now as much for the memories of childhood and my father who shared my interest in war, as much as for the films themselves.

As my history teachers will testify, my interest in war and revolutions continued all the way through school and I am especially proud of my A++ for a project I completed at 12 years old (complete with index and bibliography) on Wars and Revolutions of the 20th Century. I had wanted to write my whole project on the Russian Revolution - my real historical passion at the time - but Mrs Tones said it may not be a good idea to specialise so narrowly for this particular assignment.

Most of the courses I took at University (we did year-long courses then, not the bite-sized semester-long modules we teach now) in International Relations, Security Studies, Foreign Policy and most of my essays were about conflict. I wrote an assignment about the Six Day War and my tutor said it was more journalism than academic. As my ambition at the time was to be a journalist, I took this feedback as praise.

And so on to my PhD which used as case-studies crises and wars between 1956 and 1965, specifically the Suez Crisis, the Hungarian Uprising, the Cuban Missile Crisis and the beginning of the American involvement in Vietnam. In Phil Taylor, an historian, I had a supervisor who understood my language and my passion.

Now I communicate my passion to my students. My modules on International Crises (basically War and the Media Since 1991) and Communication and Conflict convey the way the media and communications have been central to the way nations and individuals conduct war against one another, seek to hurt and kill each other, and in short demonstrate their inhumanity. I warn the students at the start of the module that I will show them a series of harrowing pictures and video clips, but only when I am sure that such graphics reinforce the message of the lecture. I never intend to shock or offend, but perhaps sometimes we need to shock in order to persuade the world to change. I feel I am losing this battle, just as I felt deflated on the morning of 1 January 2000 when, at the dawn of a new millennium with all its hopes and possibilities, the headline news was of war, death and destruction in Chechnya; nothing had changed overnight as the world moved from one age to another. The world keeps turning.

One of the issues I discuss with students is our de-sensitisation to horror. Is it correct to argue that the more we see graphic images on TV or in the movie theatres, the less we care and the more familiar and usual such pictures become? I don't think so. Every year I show my students the same harrowing footage from Gulf War One - an Iraqi soldier burnt beyond recognition sitting atop a tank on the so-called Highway of Death; Hutus hacking Tutsis to death in the killing fields of Rwanda; mass graves in Bosnia and Kosovo; the traumatic events of 9/11. Every year without fail I choke when I watch again the second plane smashing into WTC Tower 1 and I have to turn my head from the students so they cannot see that I am almost crying. By the end of the module, I am exhausted from talking about and viewing again such carnage, and I genuinely feel emotional for the students who have been subjected to such images. We read together the memoirs of war correspondents from ages past and realise that Don McCullen's reaction is far from unique. All share an intense hatred of war, all are scarred in some way by the butchery they have witnessed.

Above my desk in my office I have photos of some of the Cathedrals and churches I have visited over the last few years, in particular the Sacre Coeur and Notre Dame in Paris, two of Man's most stunning creations. I last visited both alone on Easter weekend 2010, and despite being an atheist I was calmed by the atmosphere and found comfort in just being there, quietly absorbing the scene around me. I have deliberately positioned the photos of these Cathedrals above my desk so I can see them while I am working. I explain to my students that everyday I read, write and talk about man's inhumanity to man, and these pictures remind me that Man is also capable of genius, creativity and beauty.

I refuse to believe that man is naturally evil and that he is, by instinct, a violent creature; and although I love George Orwell with my heart and soul, I cannot agree with him that 'All art is propaganda'. These Cathedrals and Churches - and mosques, synagogues, monuments, art, music, theatre, literature, dance, the movies - all demonstrate that man is capable of finding the most beautiful, inspiring and rewarding ways to express his genius. And anyone who has visited the Pyramids in Egypt, the cave paintings of Lascaux, or has just wandered around the British Museum will know that Man has been producing the most amazing artifacts, monuments and buildings for thousands of years. Sitting on Easter Sunday in the Sacre Coeur I realised: this Cathedral and all the other places of worship I have visited (most recently Istanbul's Hagia Sophia took my breath away) are not really statements of Man's adoration of God or an expression of his religious devotion; they are in fact declarations of Man's own creative genius which in many ways elevates him to his own Heaven. Many of these buildings were created in the so-called Dark Ages which is a completely inappropriate term for such an imaginitive time in our history

|

| Inside the Sacre Coeur |

Although I believe in no deity, I hope that I am a spiritual man. I have no faith except faith in my fellow man - his compassion and his intellect. I do find solace in the silence of these buildings. I gaze around at the wonder of 14th, 15th and 16th Century architecture, the craftsmanship, the patience, care and skill that has built them, and I find comfort in the realisation that man's inhumanity to man is only a part of our History.